New trends in global value chains

Global value chains have become increasingly popular forms of manufacturing. Now accredited by the IMF and World Bank, it’s a common theme to adopt international production policies. But, is it a wise move? Who stands to benefit from a perceived boost in world trade? Carry on reading to find out more about the strengths and weaknesses of global value chains.

What are the global value chains?

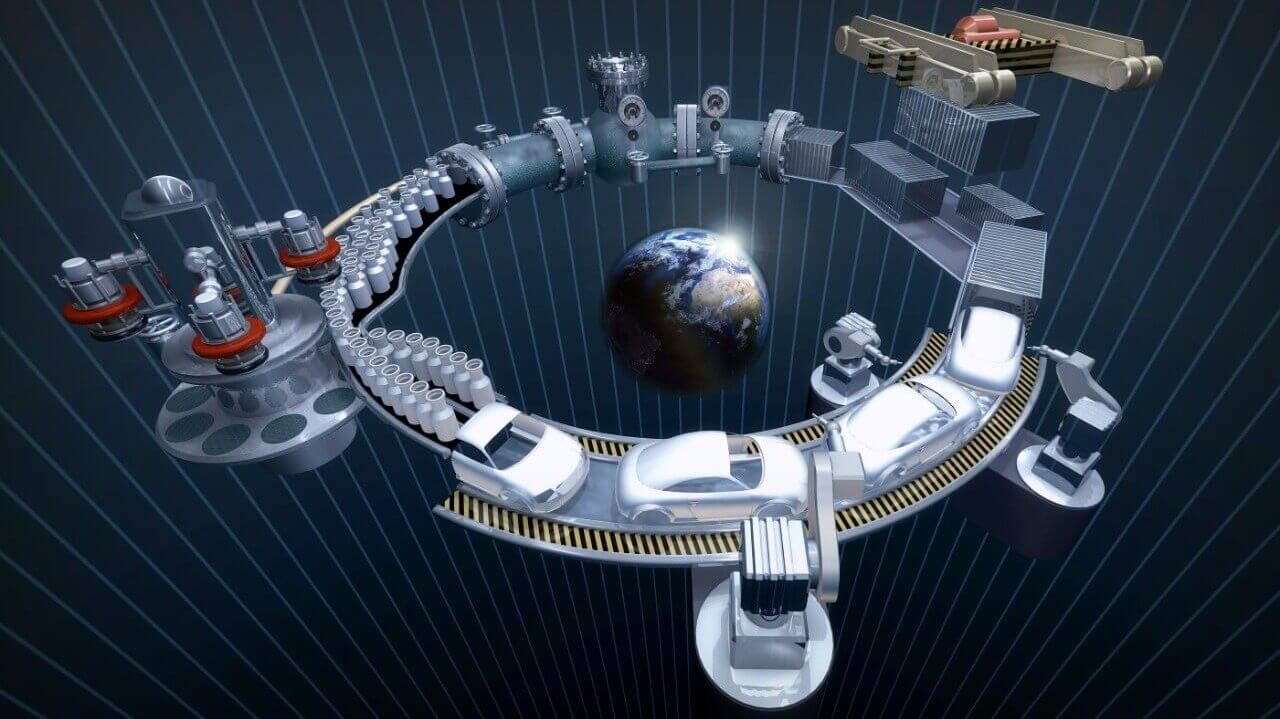

In short, global value chains are production processes that are located across a variety of countries. Years ago, products and services were mainly manufactured in one country, and this was a source of pride – for example, British steel or American-made cars.

Today, this has all changed. As of now, a single product is often manufactured in multiple countries before it reaches the high street and online shelves.

How do companies do it?

Through outsourcing and offshoring of activities. In 2019, 68% of US companies and 42% of UK firms are using outsourcing to their advantage. Instead of asking outsourcers to take care of a whole process, businesses are now chopping up manufacturing and divvying up the jobs around the world.

The result, in the eyes of manufacturers, is an increase in quality. By offshoring each tiny element of the process to the best person for the job, the standard should be higher. In the end, the final product will add more value to the customer.

What are the benefits of GVCs?

According to experts, trade liberalisation is essential for competition, innovation, and development. Here’s how global value chains help with these elements through the fostering of international production and world trade.

More trade

A simple yet effective by-product of global value chains is increased trade between countries. To add value, nations need to swap information and skills to create the highest possible quality products. And, the only way is to strike more deals with the people on the other side of the world who possess intelligence. In terms of imports and exports, everyone benefits because the importation of goods and services is as vital as exporting to successful GVCs.

Increased knowledge

By making things together, there is more dissemination of information regarding manufacturing. It’s almost impossible to craft a quality product or service without communication and teamwork. So, when two or more countries come together and interact, they learn how other nations tackle different processes. When this happens, states can increase their knowledge in certain areas and strengthen their abilities. This occurs regardless of the country because every nation has something to learn.

Rise in job opportunities

Job opportunities that didn’t exist are now available thanks to global value chains. Places throughout the globe are creating jobs for people that need it the most. Yes, it’s most beneficial for lower-economically-developed nations, but the rich ones benefit too. Even in Western Europe, there is a divide between areas within a country that provide quality jobs. GVCs change this as manufacturing plants can be situated anywhere, boosting the local economy.

Sustained growth

A result of all of the above is sustained growth. Increased knowledge leads to countries transforming into specialists, which, in turn, results in more trade between nations. Once you factor in job production and the effects on the national and local economies, sustained growth is almost inevitable.

Of course, there are no guarantees. Countries need to engage with global value chains effectively and consistently if they are going to take advantage. Those that don’t will reap what they sow.

Who benefits the most?

While every country benefits in some form – they wouldn’t take part if they didn’t – there are levels to GVCs. For the most part, developing nations get to exploit the opportunities the most. While GVCs generate growth across the board due to the importation of skills and technology, as well as boosting employment, the maximum results are in LCD nations.

This is because they move away from lower-value-added processes and into the higher-value-added ones. Also, there is more investment in technology, not to mention the increase in their knowledge bases as a result of working with other nations. While richer countries can expect these features to aid them, they already have these elements in place. Developing countries don’t, so the effects are twice as powerful. The opportunities allow them to increase their productivity levels by a significant margin because there is more capacity.

Developed nations see a positive impact in terms of value added by services rather than in gross terms. The likes of the US, UK, France, and Germany get a 50% increase in exports from their service sectors.

Are there any drawbacks?

The short answer is yes. Logistical demands don’t always work in favour of workers. Although social upgrading for regular employees is a thing, there is the flip side of the coin. Social downgrading happens to irregular workers as a result of changing demands and short lead times. To deal with them, factories take on people on non-fixed, short-term contracts that are casual and not lucrative. This leads to discrimination in the form of wages and treatment, which results in poorer working and living conditions.

Also, the cost of imports shouldn’t be overestimated. Tariffs exist, even though countries go out of their way to keep them low. When an item crosses multiple borders, the price it pays in terms of tariffs is several times higher. During a trade war, the import costs are enough to prevent businesses from using a global chain value model completely. And, trade wars are a consequence of GVCs.

A once developing nation, China, is now a major player that threatens world trade across the globe. To stop the influx of cheap materials, countries increase the import tariff and make it more expensive. Unfortunately, a tit-for-tat policy develops as each part of the chain decides to up their costs in retaliation.

Conclusion

Global value chains bring advantages, especially for developing countries. However, the policy seems to be declining FDI flows have fallen by 13%, and foreign value-added content is at an 11 year low. Even the IMF states: “gains appear more significant for upper-middle and high-income countries.”